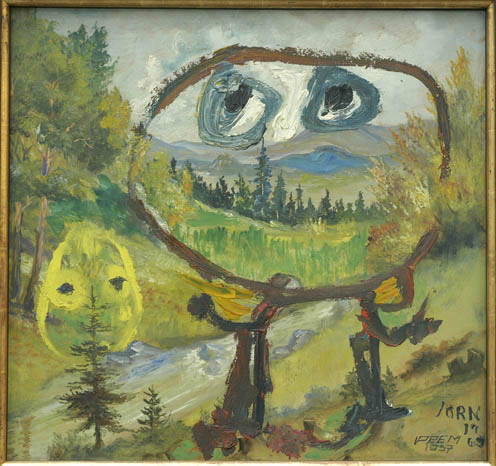

PEINTURE DÉTOURNÉE (JORN, Mai 1959)

PEINTURE DÉTOURNÉE

Destiné au grand public. Se lit sans effort.

Soyez modernes,

collectionneurs, musées.

Si vous avez des peintures anciennes,

ne désespérez pas.

Gardez vos souvenirs

mais détournez-les

pour qu'ils correspondent à votre époque.

Pourquoi rejeter l'ancien

si on peut le moderniser

avec quelques traits de pinceau ?

Ça jette de l'actualité

sur votre vielle culture.

Soyez à la page,

et distinguésdu même coup.

La peinture, c'est fini.

Autant donner le coup de grâce.

Détournez.

Vive la peinture.

Asger JORN, « Peinture détournée », Paris, Galerie Rive-Gauche, mai 1959

***

Détourned Painting

INTENDED FOR THE GENERAL PUBLIC. READS EFFORTLESSLY.

Be modern,collectors, museums.

If you have old paintings,do not despair.

Retain your memoriesbut détourn themso that they correspond with your era.

Why reject the oldif one can modernize itwith a few strokes of the brush?

This casts a bit of contemporaneityon your old culture.

Be up to date,and distinguishedat the same time.

Painting is over.

You might as well finish it off.

Détourn.

Long live painting.

INTENDED FOR CONNOISSEURS. REQUIRES LIMITED ATTENTION.

All works of art are objects and should be treated as such, but these objects are not ends in themselves: They are tools with which to influence spectators. The artistic object, despite its seemingly objectlike character, therefore presents itself as a link between two subject, the creating and provoking subject on the one hand, and the receiving subject on the other. The latter does not perceive the work of art as a pure object, but as the sign of a human presence.

The problem for the artist is not to know if the work of at should be considered as an object or as a subject, since the two are inseparable. The problem is to capture and to formulate the desired tension in the work between appearance and sign.

The conception of art implicit in "action painting" reduces art to an act in itself, in which the object, the work of art, is a mere trace, and in which there is no more communication with the audience. This is the attitude of the pure creator who does nothing but fulfill himself through the materials for his own pleasure.

This attitude is irreconcilable with an interest in the object as such, the work of art in its anonymity, that is, the experience of pleasure in its purity when facing a sculpture whose country of origin is unknown or whose period is uncertain. here the object floats freely in space and time. My preoccupation with objectivity and subjectivity is situated above all between these two poles, or more precisely between my will and my intelligence. I must admit that as far as the third attitude is concerned, that of the spectator, it does not concern me much. Whether one intends it or not, in the end it is to him that everything happens.

The classic and Latin concept has always been accorded a primacy to the object whereas the oriental concept ascribes everything to the subject. Ever since the establishment of the internal tension of European culture, the gothic, or northern, concept attempts to play within the dialectic of the two opposites. Therefore I am not limited by such a previously made choice.

The result is that this perspective leads one necessarily to consider all creations simultaneously as reinvestments, revalorizations of the act of humanity. The object, reality, or presence takes on value only as an agent of becoming. But it is impossible to establish a future without a past. The future is made through relinquishing or sacrificing the past. He who possesses the past of a phenomenon also possesses the sources of its becoming. Europe will continue to be the source of modern development. Here, the only problem is to know who should have the right to the sacrifices and to the relinquishments of this past, that is, who will inherit the futurist power. I want to rejuvenate European culture. I begin with art. Our past is full of becoming. One needs only to crack open the shells. Détournement is a game born out of the capacity for devalorization. Only he who is able to devalorize can create new values. And only there where there is something to devalorize, that is, an already established value, can one engage in devalorization. It is up to us to devalorize or to be devalorized according to our ability to reinvest in our own culture. There remain only two possibilities for us in Europe: to be sacrificed or to sacrifice. It is up to you to choose between the historical monument and the act that merits it.

THE EVIDENCE OF PREMEDITATION.

IN 1939 I wrote my first article ("Intime banaliteter" [Intimate banalities] in the journal Helhesten) in which I expressed my love for sofa painting(1), and for the last twenty years I have been preoccupied with the idea of rendering homage to it. Thus I act with full responsibility and after extensive reflection. Only my current situation has enabled me to accomplish the expensive task of demonstrating that the preferred sustenance of painting is painting.

In this exhibition I erect a monument in honor of bad painting. Personally, I like it better than good painting. But above all, this monument is indispensable, both for me and for everyone else. It is painting sacrificed. This sort of offering can be done gently the way doctors do it when they kill their patients with new medicines that they want to try out. It can also be done in barbaric fashion, in public and with pomp. This is what I like. I solemnly tip my hat and let the blood of my victims flow while intoning Baudelaire's hymn to beauty.

NOTES

1. There, I wrote:

Those who try to combat the production of painting are the enemies of today's best art. These forest lakes on colored paper, hanging in gilded frames in thousands of apartments, are among the most profound artistic inspirations.

The great masterpieces are nothing but accomplished banalities, and the deficiency of the majority of banalities is that they are not complete. These works do not push banality to the limit of its profundity, they fail to explore the full extent of its consequences; instead they rest on a foundation of aestheticism and spirituality. What one calls natural is liberated banality, obviousness.

Nowhere else but in Paris does one find gathered together so many things of bad taste. This is the very secret which explains why Paris remains the place where artistic inspiration is alive.

Originally appeared in the Exhibition catalogue for Asger Jorn's show at Galerie Rive Gauche (May 1959).

Translated by Thomas Y. Levin.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home