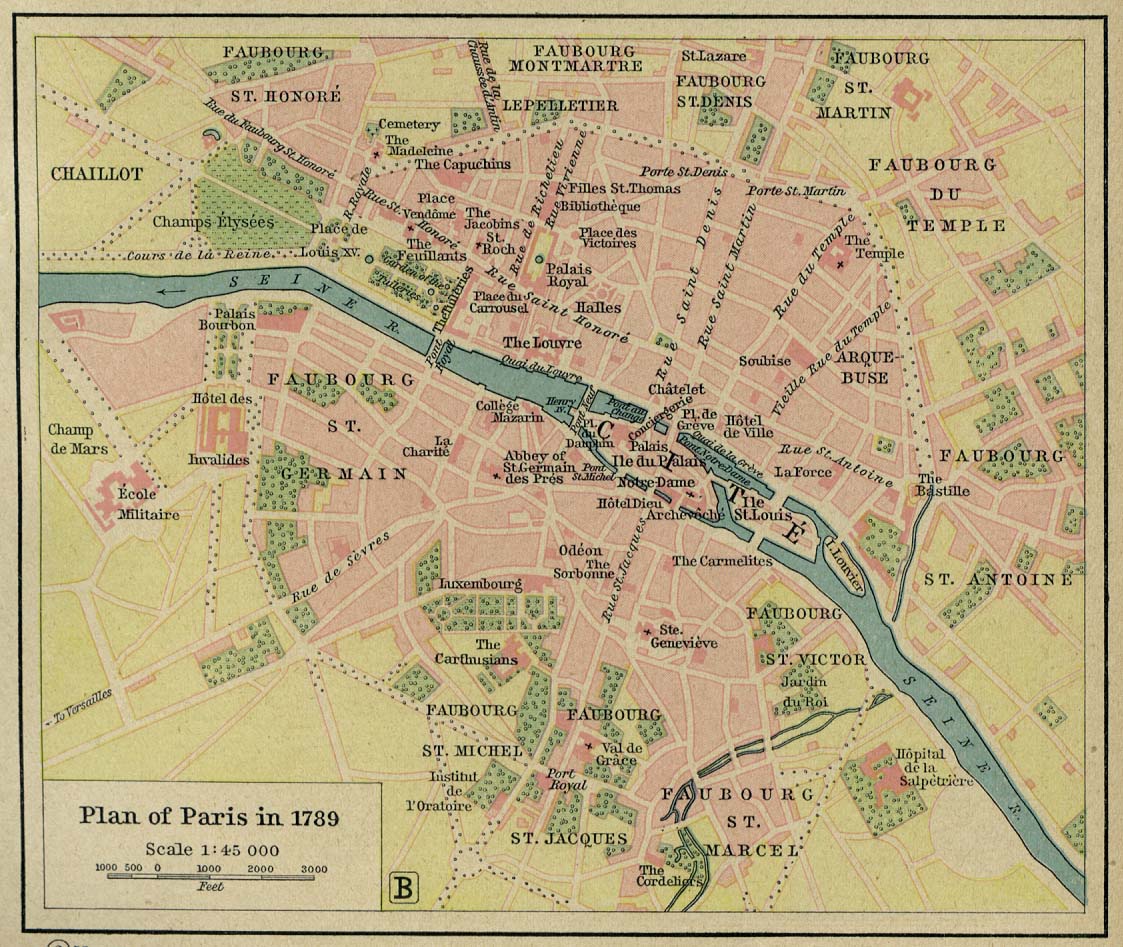

HURLEMENTS EN FAVEUR DE SADE

HURLEMENTS EN FAVEUR DE SADE (Première version,

ION, numéro 1, avril 1952. Directeur : Marc-Gilbert GUILLAUMIN)

Guy-Ernest DEBORDBANDE SONORE & IMAGES

(Les mots en capitales seront écrits en blanc sur l’écran noir.

Le terme

rencontres désigne uniformément toutes les images dont l’érotisme ne sera tempéré que par l’existence, scandaleuse et à peine croyable d’une police.)

***

Au début de cette histoire, il y avait des gens faits pour l’oublier ; et le beau temps qui a été plus perdu que dans un labyrinthe.

Images : Défilé de troupes de l’Armée des Indes au siècle dernier.

(

Long silence.)Images : Écran noir.Gros plan de Guy-Ernest Debord.Écran noir.

Croyait que le soir passerait tout entier dans sa bouche. Mais il était malade à cause de cette impossibilité d’être compris ; et au hasard des connaissances et des ruptures, il trouvait peu à peu une métaphysique du refus.

Images : Gros plan d’une fille suçant une glace. Panoramique ascendant de la Tour Saint-Jacques, répété plusieurs fois.

Qu’est-il devenu ?

(

Dernière strophe de Marche de François Dufrêne, dite très doucement.)

Arthur Cravan sous des eaux profondes.

((-

Dit par un noir américain.-))

Images : Vues d’un cuirassé de la bataille de Tsoushima.

Sa trace se perd à peu de temps de là dans le golfe du Mexique où il s’est engagé de nuit sur une embarcation des plus légères.

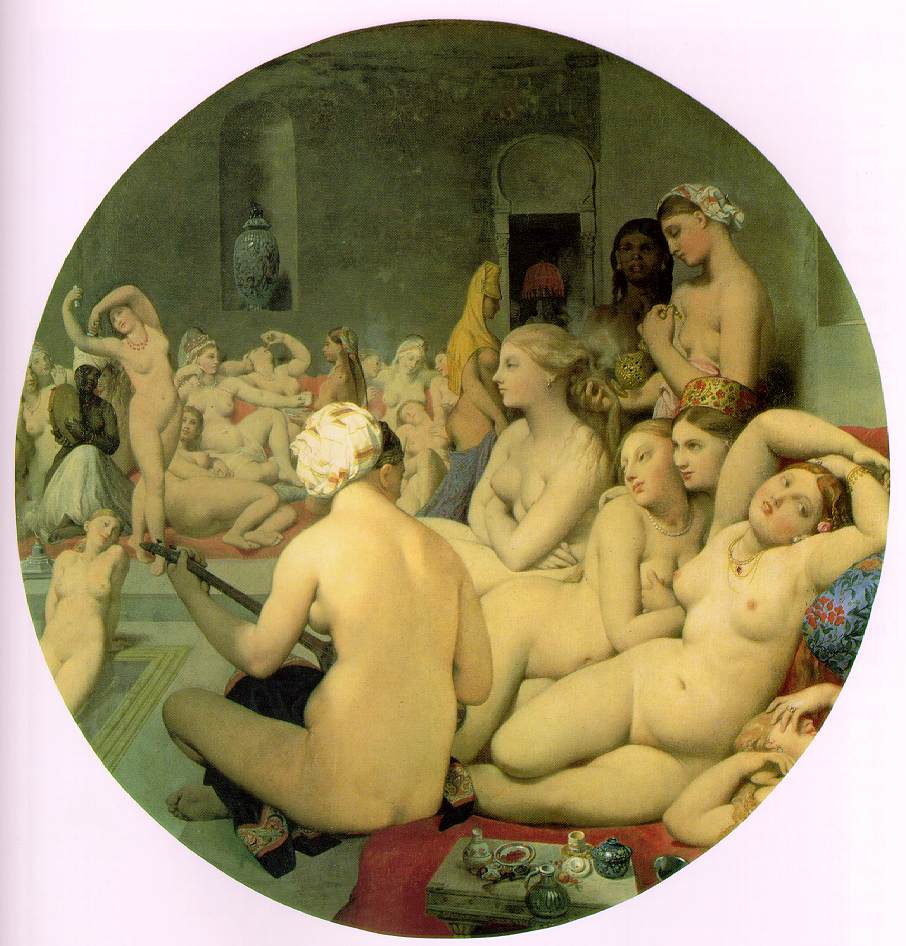

Images : Rencontres.

(

Cors de chasse, d’Apollinaire, qu’accompagne une improvisation supersonique de Marc,O.)

Images : Défilé de troupes de l'Armée des Indes.Emmanuel Dieu attend l’heure sidérale que sa tête s’en aille.

Images : Rencontres.

Une science des situations est à faire, qui empruntera des éléments à la psychologie, aux statistiques, à l’urbanisme et à la morale. Ces éléments devront concourir à un but absolument nouveau : une création consciente de situations.

Images : Scènes d'émeutes.

Je n’aime pas le cinéma, mais une insurrection qui m’est promise chaque matin quand je revois Violette Nozières, ou le monument élevé à la mémoire de Serge Berna.

Images : Rencontres.Une fillette de douze ans sourit en passant et descend dans une bouche de métro.Vues de Notre-Dame sous divers angles.(

Un air de Vivaldi commence.)

Images : Écran noir.

Se souvenait de ce bar où il attendait que le demi-siècle change, en pensant à tout ce qui allait finir une fois de plus et

Images : Gros plan de Guy-Ernest Debord.

Une fille assise, le visage contre une table où ses cheveux s’étendent en avant.

(

Long silence.)

Images : Écran noir.

toujours attachés à l’heure, aux dernières secondes, jusqu’à minuit.

Images : Écran noir.Des yeux en gros plan.Écran noir.(

La musique continue un instant, puis s’arrête.)

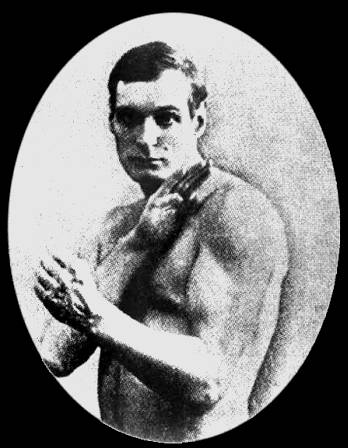

Images : Match de Boxe.

Alors il sortit dans la rue froide, et les sirènes se mirent à hurler.

Images : Lacher de parachutistes.

((-

Mots épelés.-))

T,E,L,L,E,M,E,N,T, V,I,D,E, À, H,U,R,L,E,R, À, H,U,R,L,E,R,

Images : pellicule brossée jusqu'à la destruction complète de l'image.

(

Coups de sifflets.)

Sa mémoire la retrouvait toujours, dans un éblouissement brûlé par tous les feux d’artifice du sodium au contact de l’eau.

Images : Visage d'une fille endormie.

Savait bien qu’il ne resterait rien de ces gestes dans une ville qui tourne avec la Terre, et la Terre tourne dans sa Galaxie qui est une partie assez peu considérable d’un îlot qui fuit l’infini hors de nous-mêmes.

Images : Écran noir.Gros plan de Guy-Ernest Debord.Écran noir.Match de boxe.

((-

Mots épelés.-))

C,O,R,P,S, À, C,O,R,P,S, P,E,R,D,U,S,

Il se promenait et

(

Silence.)

Images : Écran noir.Guy-Ernest Debord en plan américain boit un verre.

plus désespéré que

Images : Écran noir.Vues de plusieurs cheminées d'usines.

(

Fragments de « J’interroge et j’invective », poème à hurler de François Dufrêne.)

Images : Pellicule brossée.

La première merveille est de venir devant elle sans savoir lui parler. Les mains prisonnières ne bougent pas plus vite que les chevaux de course filmés au ralenti, pour toucher sa bouche et ses seins ; en toute innocence, les cordes deviennent de l’eau, et nous roulons ensemble vers le jour.

Images du ciel nocturne, au télescope.

((-

Les phrases soulignées seront dites par une fille à l’accent bulgare*.-))

Je crois que nous ne nous reverrons jamais.

Images : Rencontres, au ralenti.

Près d’un baiser les lumières des rues de l’hiver finiront.

En ce moment à Tahiti, c’est l’aube.

Paris était très agréable à cause de la grève des transports.

Jack l’Éventreur n’a jamais été pris.

Il est amusant, le téléphone.

Quel amour-défi, comme disait Madame de Ségur.

Je vous raconterai des histoires de mon pays qui font très peur, mais il faut les raconter le soir pour avoir peur.

Ma chère Ivich, les quartiers chinois sont malheureusement moins nombreux que vous ne le pensez. Vous avez quinze ans.

Les couleurs les plus voyantes un jour ne se porteront plus.

Je vous connaissais déjà.

Séoul et d’autres nébuleuses.

La forêt vierge l’est moins que vous.

Guy, j’ai si froid.

Le démon des armes, vous vous souvenez, c’est cela. Personne ne nous suffisait. Que voudront dire plus tard, Boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle, l’inceste et l’écolière ?

(

Hurlements.)

Images : Scènes d'émeutes.

Tout de même…

La grèle sur les bannières de verre. On s’en souviendra de cette planète.

Un monde de cris a été perdu.

((-

répété trois fois mécaniquement et légèrement crescendo.-))

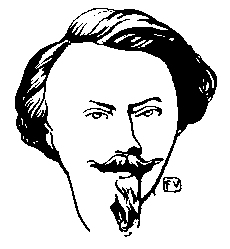

Images : Isou, en gros plan, sourit à la salle.

Images : Écran noir.

pensait à quelques lignes d’un journal, en 1950.

Images : Gros plan de Guy-Ernest Debord.Écran noir.Scènes d'émeutes.

((-

Voix monotone.-))

Une jeune vedette de la radio se jette dans l’Isère.

Images : Rencontres.

Grenoble. La petite Madeleine Reineri, douze ans et demi, qui animait, sous le pseudonyme de Pirouette, l’émission radiophonique des Beaux Jeudis, au Poste Alpes-Grenoble, s’est jetée dans l’Isère, vendredi après-midi, après avoir déposé son cartable sur la berge de la rivière.

((-

Doucement.-))

VARALINE

VARADALINE

SIANE MARIALE MALIVOLANE.

Images : Corps de jeunes gens tués dans les rues d'AthènesMa petite sœur, nous ne sommes pas beaux à voir. L’Isère et la misère continuent. Nous n’avons pas de pouvoirs.

Écrits en blanc sur l'écran noir : ET LA JEUNESSE SE DÉCOMPOSERA UN PEU PLUSLe Soulèvement de la Jeunesse…

Images : Gros plan de Marc,O.

(

Coups de sifflets stridents ; puis chœur lettriste en fond sonore dominé par des cris et des coups de sifflets.)

Images : Intérieur du Mabillon avec ses clients habituels.

Considérations sur les rapports sexuels en France vers la fin de l’ère chrétienne.

Presque toutes les filles âgées de moins de quinze ans nous sont interdites.

La plupart des perversions sont mal vues du grand public.

Images : Match de boxe.

La police parisienne est forte de trente mille matraques.

Il y a encore beaucoup de gens que le mot de morale ne fait ni rire, ni crier.

(

Fin du chœur lettriste.)

Christiane est en prison.

L’ordre règne et ne gouverne pas.

((-

Mécaniquement.-))

La psychologie tridimensionnelle, ou le complexe architectural défini comme moyen de connaissance.

Images : Vues extérieures du Musée de Cluny.

Le chien andalou s’est enfermé dans les maisons du sommeil, comme un argonaute étranglé.

Images : Scènes d'émeutes.

Tant d’indulgence et la victoire de Kossovo, les plaies secrètes. Au coin de la nuit les marins font la guerre ; et les bateaux dans les bouteilles sont pour toi qui les avais aimés. Tu te renversais dans la plage comme dans les mains plus amoureuses que la pluie, le vent et le tonnerre mettent tous les soirs sous ta robe.

La vie est belle l’été à Cannes.

Le viol, qui est défendu, se banalise dans nos souvenirs.

Quand nous étions sur le Chattanooga.

Oui. Bien sûr.

Images : Pellicule brossée.

Et l’ensablement de ces visages qui furent les éclatements du désir, comme l’encre sur un mur, qui furent des étoiles folles.

Que le gin, le rhum et le marc coulent comme la grande Armada.

Ceci pour l’éloge funèbre.

Mais tous ces gens étaient vulgaires.

(

Applaudissements et coups de sifflets simultanément.)

Images : Écrits en blanc sur l'écran noir : LE DÉSORDRE POUR LE DÉSORDRE.

Le supplice de la caresse recommence avec elle et la faiblesse se refuse et augmente.

Images : Match de boxe.

La chute verticale vide un tonneau des Danaïdes, un tonneau de gel et de lèvres.

Images : Pellicule brossée.

Le tapis tourne dans une autre dimension du temps, se tache.

Comme un sucre qui fond.

Images : Lacher de parachutistes.

La musique borne le rouge et le vert des signaux.

La nuit est à toi.La musique triomphale s’élargit.

Images : Rencontres.

Il est couché à la nage dans un fleuve très chaud, une mer d’huile.

Déjà ce n’est plus qu’une affaire de cheveux.

Je n’ai jamais beaucoup aimé la Wodka, ni les confidences.

((-

Voix monotone.-))

La petite Madeleine Reineri, douze ans et demi, qui animait, sous le pseudonyme de Pirouette, l’émission radiophonique des Beaux-Jeudis, au Poste Alpes-Grenoble, s’est jetée dans l’Isère…

Images : Lacher de parachutistes.

Mademoiselle Reineri, dans le quartier de l’Europe, vous avez toujours votre visage étonné et ce corps, la meilleure des terres promises.

Images : Plaque de la rue de Lisbonne.Progression de l'infanterie française en Indochine.

Les dialogues répètent comme le néon leurs vérités définitives.

(

Solo lettriste improvisé sur un râle.)

Images : Écrits en blanc sur l'écran noir : JE T’AIME.CE DOIT ÊTRE TERRIBLE DE MOURIR.AU REVOIR.TU BOIS BEAUCOUP TROP.QUE SONT LES AMOURS ENFANTINES ?JE NE TE COMPRENDS PAS.

Je savais. À une autre époque je l’ai beaucoup regretté.

Images : Écrits en blanc sur l'écran noir : VEUX-TU UNE ORANGE ?LES BEAUX DÉCHIREMENTS DES ÎLES VOLCANIQUES.AUTREFOIS.

Je n’ai plus rien à te dire.

Images du ciel nocturne au télescope.

(

Fin de l’improvisation lettriste.)

Après toutes les réponses à contretemps, et la jeunesse qui se fait vieille, la nuit retombe de bien haut.

(

Cris de François Dufrêne :) Images : Scènes d'émeutes.

VI

XIII ad lib.

KWORXE KOWONGUE KKH

WOZ BU WONZ GGH

WEXPI GWÈGNS

PIV

HIGNS CHTABUHI

HIGNS

STOBOHU STOBOHU KAX

GONX

KWORXE KOWONGUE KKH

WOZ BU WONZ GGH

Images : Pellicule brossée.

TIYNDOLLF, TIYNDOLLF,

TIYNDOLLF (bis).

GLILEUS, GLILEUS, GLILEUS,

GLILEUS, GLILEUS (bis).

CHTAM, CHTAM, CHTAM,

CHTAM, BAOUMPE (bis).

KFRACHIKANNKLE

KLEX

XIV

KLWATWORZZ…

CHFARBONR CHFIDRE,

CHFIDRE, CHFIDRE (bis).

CHFARBONR CHGLIFT !

VI

À propos de ces souvenirs j’ai détruit le cinéma, parce que c’était plus facile que de tuer les passants.

((-

Ici le commentaire se limite à la lecture de divers articles du Code Civil et d’extraits d’un manuel de Littérature Française.-))

Images : Pendant le reste du film, succession d’images absolument quelconques ; en dehors de toute intention d’humour, de montage, ou de provocation.

Les mondes poétiques se ferment et s’oublient en eux-mêmes.

Images : Visage d’une fille masqué par ses cheveux.

Sur la place Gabriel-Pomerand le brouillard dissimule des rendez-vous qui tournent au suicide.

Images : Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés, déserte.

Nous vivons en enfants perdus, nos aventures incomplètes, nos aventures démesurément petites.

Images : Rencontres.

La dérive des continents éloigne chaque jour davantage une fille aussi belle de Gilles de Rais.

Images : Guy-Ernest Debord sort de l’Escapade et descend la rue Dauphine.

Vous savez, tout cela n’a pas d’importance.

Images : Écran noir.

(

Un court silence, puis des cris très violents dans le noir.)

_________________

* ici, en caractères gras

Le Palais idéal

Le Palais idéal