Hurlements en faveur de Sade. 1952, 1h04. Films lettristes. Voix de Gil J. Wolman, Guy-Ernest Debord, Serge Berna, Barbara Rosenthal, Jean-Isidore Isou. ; Réalisation : Guy-Ernest Debord ; Numéro de visa : 113959; Longueur : 1751 m ; Film noir & blanc

Hurlements en faveur de Sade. 1952, 1h04. Films lettristes. Voix de Gil J. Wolman, Guy-Ernest Debord, Serge Berna, Barbara Rosenthal, Jean-Isidore Isou. ; Réalisation : Guy-Ernest Debord ; Numéro de visa : 113959; Longueur : 1751 m ; Film noir & blanc

Sur le passage de quelques personnes à travers une assez courte unité de temps. 1959, 20 minutes, 35 mm, film noir & blanc. Dansk-Fransk Experimentalfilmskompagni. Réalisation : Guy-Ernest Debord ; Chef opérateur : André Mrugalski ; Montage : Chantal Delattre ; Assistant-réalisateur : Ghislain de Marbaix ; Assistant-opérateur : Jean Harnois ; Script : Michèle Vallon ; Machiniste : Bernard Largemain; Speakers : Jean Harnois, Claude Brabant et Guy-Ernest Debord. Musique : Haendel (Thème cérémonieux des aventures) ; Delalande (Thème noble et tragique - basson en solo) ; Delalande (Allegro d'une musique de cour)

Sur le passage de quelques personnes à travers une assez courte unité de temps. 1959, 20 minutes, 35 mm, film noir & blanc. Dansk-Fransk Experimentalfilmskompagni. Réalisation : Guy-Ernest Debord ; Chef opérateur : André Mrugalski ; Montage : Chantal Delattre ; Assistant-réalisateur : Ghislain de Marbaix ; Assistant-opérateur : Jean Harnois ; Script : Michèle Vallon ; Machiniste : Bernard Largemain; Speakers : Jean Harnois, Claude Brabant et Guy-Ernest Debord. Musique : Haendel (Thème cérémonieux des aventures) ; Delalande (Thème noble et tragique - basson en solo) ; Delalande (Allegro d'une musique de cour)

Critique de la séparation. 1961, 20 minutes, 35 mm, film noir & blanc. Dansk-Fransk Experimentalfilmskompagni. Réalisation : Guy-Ernest Debord ; Chef opérateur : André Mrugalski ; Montage : Chantal Delattre ; Assistant-opérateur : Bernard Davidson ; Script : Claude Brabant ; Machiniste : Bernard Largemain ; Speakers : Caroline Rittener et Guy-Ernst Debord. Musique : Couperin (Marche du Régiment de Champagne) ; Bodin de Boismortier (Allegro du Concerto à 5 parties en mi mineur, opus 37)

Critique de la séparation. 1961, 20 minutes, 35 mm, film noir & blanc. Dansk-Fransk Experimentalfilmskompagni. Réalisation : Guy-Ernest Debord ; Chef opérateur : André Mrugalski ; Montage : Chantal Delattre ; Assistant-opérateur : Bernard Davidson ; Script : Claude Brabant ; Machiniste : Bernard Largemain ; Speakers : Caroline Rittener et Guy-Ernst Debord. Musique : Couperin (Marche du Régiment de Champagne) ; Bodin de Boismortier (Allegro du Concerto à 5 parties en mi mineur, opus 37)

Guy Debord and the Problem of the Accursed

Guy Debord and the Problem of the AccursedAsger JORN

". . . outlaws impelled by that energy springing from bad passions, alone capable of overthrowing the old world and giving back to the forces of life their creative liberty."Alain Sergent and Claude Harmel,

Histoire de l'Anarchie

"It would have been better for mankind if this man never existed." This is what

The Gentlemen's Magazine wrote on the occassion of the death of Godwin, who was an inspiration to Shelley, Coleridge, Wordsworth, William Blake, and many others, just as Proudhon is the inspiration for Courbet's painting. From this group comes a large part of modern poetry, the "plein air" school in landscape painting, Impressionism, and a whole continuous creative development whose continuation belonged and still belongs to the forces of life, constituting creative freedom itself. But such a development cannot be understood if one separates it from its solidarity with this bad passion that is "alone capable of overthrowing the old world" - the passion carried by creative rule-breakers who are cursed as such.

This state of affairs no longer is at odds with society's general attitude toward modernism. Paradoxically, the general sympathy toward modernism since the turn of the century, and especially since World War II when it was proclaimed that "the accursed artist no longer exists," represses these creative forces even more radically. The reality of social malediction is wrapped in a tranquilizing and antiseptic appearance of emptiness:

the problem has disappeared ; there never was a problem. At the same time, the journalistic label of "accursed" becomes, on the contrary, an immediate valorization. It is enough to get yourself cursed, to be all the rage. And this is fairly simple, since any kind of aggression provokes curses from its victim. Thus the very principle of the accursed is altered; we rediscover the simple romantic notion of the unrecognized genius. He's the thinker whom one willingly considers as "ahead of his time," and one attempts, further, to leave him unrecognized for as brief a time as possible.

I believe that no other creative person in the world reveals to us the futility of such false explanations as does the enigmatic personality who is Guy Debord. We can already read in certain critical analyses - the most well-informed of our era - that he is considered as one of the greatest innovators in the history of cinema. Thus those who are knowledgeable in this area are able to recognize his true stature. And so we cannot claim that he is unrecognized. The hitch is between this confidential appreciation and his reputation in the world of "gentlemen," where one would like to recycle, as soon as possible, the same obituary for Debord as was used for Godwin. We must conclude from this that valorization and malediction are clearly simultaneous. Debord is of his time; he can not

"be bettyer than his time ; but, at best, be his time" (Hegel). But this time has become a space where strange things happen, which are not in accordance with the simplistic idea one has of the historic instant. For us, the present is not hte instant, but is, as defined by modern physics, the moment of dialogue, the time of communication between question and answer. The problem of the accursed is circumscribed in this immeasurable space, where for some people, the answer is already given, while others don't yet know the question. The methods of our era's "instantaneous" pseudo-communication obviously do not transmit the questions and the answers of this era, but, rather, a unilateral spectacle, as the Situationists have amply shown.

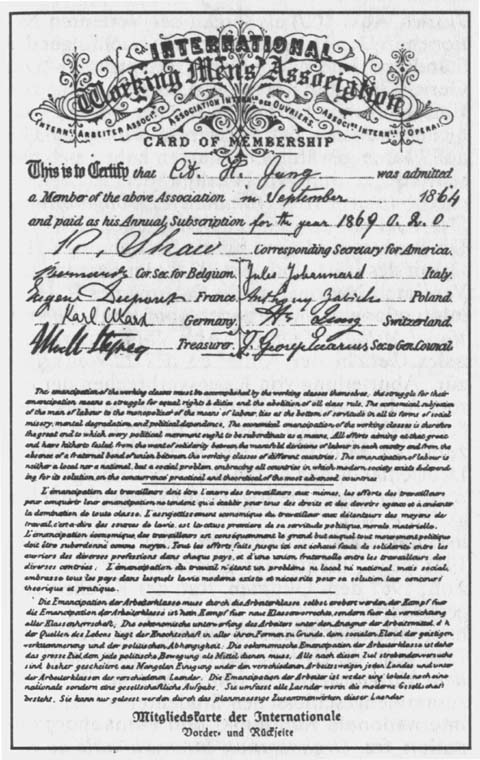

Communism was the great accursed movement of the last century. After the Russian Revolution, Marxism was officially presented as the basis of society in the Eastern Bloc, and even more cursed in the West, especially in the United States. But what is the truth of thos spectacular conflict ? John Kenneth Galbraith, who spent World War II in strategic bomb administration, who is an officer in military itellegence that and has been duly awarded various honors, admits in his book

The Affluent Society that modern capitalism, while still believing itself to be anti-socialist, today has latched onto a few of the more obviously Marxist dogmas, while ignoring their origin and still cursing Karl Marx. In a parallel development, one can see how Russian society, whether or not it believes itself to be Marxist, has managed to essentially curse Marx's doctrine, while honoring him. There are clean breaks between the person who formulates ideas, those who consciously appreciate his ideas and his value, and the spreading of these "outlaw" ideas, which return discreetly and anonymously to the forces of life through creative freedom.

Guy Debord's cinematic achievements give us an example whereby we can uncover the dominant method of suppression in all its complexity. Without the definite overthrow of cinematic art brought about by research during the lettrist era, of which Guy Debord's

Hurlements en faveur de Sade clearly represents the acme, one can rightly wonder if films like

Hiroshima mon amour could, seven years later, have been made and celebrated. But who knows? And more to the point, who can say ? Those who know it keep it quiet, so that the public at large, on a world-wide scale and including intellectuals, remains stupefied by a work considered absolutely original. Thus one does not allow oneself to recognize the subsequent regression of Resnais in the films he has made since then; such a decline is in fact typical of calculated adaptions, considering the degree of profundity allowed based on the radical creation itself. This is where the great hypocrisy necessary to the necessary to the illusion of official "modernism" sets in. A Danish literary journal

Perspektiv, uses in fact the film

Hiroshima mon amour as substantial proof that there is no renewal among the rebels. Renewal can only come from the heart of official production. And since the general public knows nothing of the creative efforts necessary to bring about such a work, everyone lashes out in good conscience against these bad boys who represent true originality, in order to cut them off permanently from creative activity. But for Debord, this is not possible. They don't realize that his filmic activity is only a random grasping of whatever tools are available, in order to make a specific demonstration of more general abilities. What stands to lose the most in this affair is simple the development of cinema.

Here we encounter another extremely important question: it seems that in every development there are crucial moments when a single act - a stroke of genius - completely changes the order of basic assumptions. And after such a moment, whether one likes it or not, whether one admits it or not, the conditions have changed

for everyone. One could also say that this change, obviously produced by the movement of general conditions and collective activities, can only be realized in the mind of a single individual. He seems to have done nothing else during his entire life but prepare for precisely that, and nothing else. And once that act is accomplished, he has nothing else to do except to see and control its effects. It is precisely this element of control that will be denied to him, and will pass to others at the moment when, profitting from this act and exploiting its attendant power, they simultaneously acquire the means to condemn its author. This phenomenon has been so common since ancient times that in certain cultures it has even become sacred. In the end it reveals what is called "the mystery of sacrifice." Today, since we must be more civilized, we no longer literally sacrifice; we curse. There is no more mystery, and the shrewdest form of sacrifice is sanctification by praise. So it is fairly clever to place Debord at the summit of the cinematographic hierarchy. Thus, it is thought, he can no longer surpass himself; the next chapter can be written by other hopefuls, the chiselers and the amplifiers. Perhaps specialization requires such a division; it has never bothered Debord - he is entertained by it. But there are others who are less amused. I am one of them. In fact, I am hardly amused by these questions of cinema. I am not talking about films that are entertainment. I am talking about the joy of witnessing the birth of something essential, yet indefinable, that each of Guy Debord's new films brings to me. He can say rhat what is done is done, that all one can do is watch the results. This is where I sense that in the unfolding of events provoled by his perspective of general change, which surpasses by far the world of cinema, he observes many things that we overlook, and whose interest he communicates to us.

To be the great, secret inspiration of

world-wide art for some ten ten years - from the silence John Cage introduced into modern music a few years after

Hurlements en faveur de Sade to the craze for communicating through comic book frames taken out o context, which has become the cutting edge of new American painting - is already not so paltry. It would be possible to continue in this way, were there not an accumulation of consequences to this intransigent activity, making Debord indespensable to the new awareness of our general situation as creative creatures. This awareness becomes inevitable with the abandonment of the officially modernist and progressive attitude that hid the true state of affairs since the end of World War II. Once this mask is stripped away, Guy Debord's secret is immediately understood.

There is no such thing as a naturally "unrecognized genius," or an unacknowledged innovator. There are only those who refuse to be known through false appearances - in blatant contradiction to who they really are. Those who do not wish to be manipulated in order to appear in public in a totally unrecognizable form, and likewise alienated, reduced to the status of instruments hostile to their own cause, or impotent, in the great human comedy. We must not limit ourselves to cursing those who themselves curse, with good reason, what is proposed to them, and who are then scorned by "gentlemen" - those same "gentlemen" who elsewhere smile at anything and everything and go so far as to cite this false stoicism as proof of theit own worth. The people of taste arbitrate behind the formal pretexts; they pretend to find simply "ill-expressed" what's new, what damns them, what says they are bad. Thus in modern culture, Guy Debord is not badly known;

he is known as the Bad.

Obviously it is not possible to curse something without having in mind something that is better, to which you are comparing what you reject. This is the secret of Guy Debord, who is the only one of the lettrists to have this vision, which explains all his undertakings. If you do not take this vision into account, if you rely simple on the established order to make your judgements, everything that he has created can only be understood as eccentric and bizarre - unbalanced, like so many others. The great lesson to be drawn from Guy Debord, since the

Potlatch era, is frankness, that it was clearly necessary to frankly curse, in a world that was more and more faked, what deserved to be cursed: the great fundamental hypocrasies, festering for centuries, nut always used as the shaky foundations of appalling vestigial forms, which claim a long future. But all of that was merely the external effect of a much deeper exploration.

Theoretically, it would be easy for the general public to be confronted with Guy Debord's work. For example, if

Hurlements en faveur de Sade were screened at all theaters in the country, this public, starting with its elite of "cinéphiles," would neither be entertained nor delighted. They would be raving mad, like the child who sees the nice piece of pie that already was making him drool thrown on the floor. These viewers might partly misunderstand this spiritual slap in the face, this tactless disciplining. But there is no doubt that it would do them good. It is here that the true problem of the accursed artist arises. This is where Debord cut through all the aesthetics of pleasantness in favor of an artistic action that provokes action, even if the action has every chance of spontaneously turning against the person who violently wrenches the spectators from their chairs, from their somnolence. Debord reveals an

importance in art, which is carefully hidden in the "beaux-arts," but is scientifically and secretly manipulated in propaganda and in advertising, both commercial and political. Thus a charade was denounced: the constructed distinction between an elite art and an art that did not even claim the name, in order not to disturb the status quo, appeared in all its falseness. This way Debord and his friends envisioned culture, as the end of a

prehistory, is in fact a way to envision current society. According to them and because of them, what is happening now in this culture comes from society

and will return to it.

To the extent that Debord has been able to occassionally express himself on art and the self-criticism of art, his works carry the same meaning and verify my interpretation : all executed swiftly, they are like experimental jottings made during the development of the general theory of

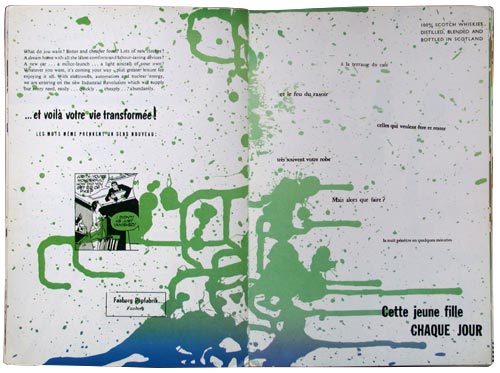

détournement. Guy Debord's callaboration in

Fin de Copenhague, a small, spontaneous book written in 24 hours, has been commented on: its effects have spread with astonishing speed, in just a few months among specialists of art books and typography, both in the United States and in Europe. This widening influence has not ceased to grow. Thus the moment was ripe for our hero to write his

Mémoires, which was done with the grating effect of broken glass - a book of love bound in sandpaper, which destroys your pocket as well as entire shelves in your library, a nice reminder of time past that refuses to end and distresses everyone with its obstinate presence. And yet these

Mémoires were more a work of relaxation, a temporary retreat, apparently. So he hurried to write his

Mémoires before beginning to appear in the world. He used them as an opening, and thus they were definitely not received with the same warmth and pleasure as greeted former agitators when they indicated through similar means that they surrendered, that they were abandoning the present. Next he undertook those curious documentaries,

On the Passage of a Few Persons Through a Rather Brief Period of Time and

Critique of Separation (

Dansk-Fransk Eksperimentalfilmskompagni) , documents on a new world-view. Apparently they are not liked. This must be due to their time-bomb effect. Debord knows all the effects, and uses them with mastery, with no constraint. But obviously those people who see only fire, and then begin to think that they were mistaken, without being able to say exactly why, feel a certain malaise.

One is never at ease before the works of Debord. Further, this is intentional. He has never smashed a series of pianos; he leaves such bizarre behavior to the clowns who imitate him, from Yves Klein's "monochrome" paintings to the recent "Visual Art Research Group," for which a certain Le Parc proposes to invent "non-action spectators, in complete darkness, immobile, not speaking." Debord has an unplumbed subtlety. He has never been accused of a flat appearance. This is the reason for the great respect - one could even say awe - that he commands in the domain we call the artistic and cultural avant-garde.

France's role in human culture takes on an entirely different appearance, according to whether it is viewed from the outside or from within. I myself see this role from the outside, and I always see him, transhistorically, as the great exception

that transforms the rules. Since the end of the war, I have not seen anyone ecept Guy Debord who, ignoring all other problems that might command attention, is concentrating exclusively, with an obsessive passion and the ability it brings, on the task of correcting the rules of the human game according to new "givens" that are imperative in our era. He is determined to carefully analyse these givens, and all the possibilities that are excluded or that open up thereafter, without any emotional attachment to a past that has given up. He demonstrates these corrections and indicates the rules he has decided to follow. He invites others who want to march in the avant-garde of this era also to follow these new rules, be he absolutely refuses to impose them throught any of the numerous means or the prestige of authority, on anyone who does not yet see their point. However, on one point he is rightly dreaded by the entire artistic milieu. He will not stand being denigrated by anyone who pretends to accept these rules but who uses them as stakes in another game - that of wordliness, in the broadest sense: being in accord with the accepted world. In such cases he is without mercy, and yet one can say that these problems of compromise or submission have arisen, sooner or later, to end nearly all his relationships. He has broken completely with these people. He has found others. This is how this man of uncommon generosity has come to figure in postar wordly mythology as the man without pity.

Finally, I will return to the paradox of the "outlaw." The exceptional person who transforms the rules excludes himself from participation in the game because he would always be the winner, since he invented the game and knows all its limits. Others can take up these rules, either by accepting their creator as the leader of the game, or by crushing him, by excluding him. This is the point where Debord rightly refuses to shoulder the full burden of absolute responsibility. The rules of his game were imposed on him by circumstances, and their complexity goes beyond his knowledge. The current Situationist movement is only the beginninf of an example of this game. By his refusal of exclusiveness and of the role of leader, Debord saves his rights to the game, as well as the very opening of the future game. In so doing, he surpasses the purely Fench conditions that set the limits of André Breton's Surrealism. Unlike the latter, the effects of Guy Debord's importance are felt everywhere, on the other side of the world, and will spread from there toward Paris, where he lives out his life unnoticed. Perhaps he has more or less chosen the difficulties of this life by doing everything necessary to continually smash any possibility of celebrity; perhaps in order to remain free in the games currently possible. Nonetheless, I believe I have justified the indiscretion I have commited with this insistent presentation. In any case, I hope so.

Originally appeared as the

preface to Guy Debord's

Contre le Cinema published by Institute Of Comparative Vandalism (1964). Translated by Roxanne Lapidus.